Ontario at a tipping point with 80,000 homeless: AMO study

Ontario is at a tipping point in its homelessness crisis. A new study reveals more than 80,000 Ontarians were known to be homeless in 2024, a number that has grown by more than 25 per cent since 2022. Photo: Association of Municipalities of Ontario

Ontario is at a tipping point in its homelessness crisis. A new study reveals more than 80,000 Ontarians were known to be homeless in 2024, a number that has grown by more than 25 per cent since 2022. Photo: Association of Municipalities of Ontario

Robin Jones has seen the impact of homelessness firsthand, both in her policing career and now as mayor of the Village of Westport and president of the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO).

As such, she was aware of how serious an issue homelessness is. But thanks to a comprehensive study released by AMO on Jan. 9, the scale of the problem has come into sharper focus.

The study reveals Ontario is at a “tipping point,” with more than 80,000 Ontarians known to be homeless in 2024. That number that has grown by more than 25 per cent since 2022.

“When I saw the 80,000, I was gobsmacked,” Jones said. “It is a tipping point that if we don’t act soon – if we don’t put a plan in place – the numbers will just continue to double or quadruple. Those numbers are just in your face.”

AMO worked in partnership with all 47 social service managers through the Ontario Municipal Social Services Association (OMSSA) and the Northern Ontario Service Deliverers Association (NOSDA). The study, conducted by HelpSeeker Technologies, indicates that without significant intervention, Ontario’s homeless population could double in the next decade, potentially affecting nearly 300,000 people in an economic downturn.

The crisis stems from decades of underinvestment in affordable housing, income support, and mental health and addictions treatment. The issue only escalates when combined with the increasing economic pressures on communities.

Ontario is the only province that shoulders social housing responsibilities on municipalities. In 2024, municipal funding for housing and homelessness exceeded $2.1 billion. Meanwhile, provincial contributions remain insufficient, barely supporting strained shelter and housing programs.

To deal with the situation, the study proposes a new approach to homelessness. It calls for a new plan that focuses on long-term housing solutions over temporary emergency measures and enforcement.

Significant Financial Investment

AMO is urging provincial and federal governments to take significant, long-term action on affordable housing, mental health and addictions services, and income supports to fix homelessness and improve Ontarians’ overall quality of life.

To end chronic homelessness, the study recommends an extra $11 billion over 10 years. These funds would support affordable housing, transitional and supportive services, and prevention programs. Additionally, $2 billion over eight years could largely end homeless encampments.

Jones isn’t blind to the financial aspects of the ask. But she also wants to reiterate AMO isn’t asking for this investment to come immediately or all at once.

“Let’s be clear, we’re not asking for $11 billion today. The problem is this big. We need a plan,” Jones said. “And that’s the approach that, as president of AMO, I’m taking to the government. We’ve done the work, we’ve got credible data, now what do we put in place?”

Deeply Troubling Statistics

Lindsay Jones is AMO’s director of policy and government relations. She agreed that the situation is at a tipping point. After all, she said, everyone knew homelessness was a problem, but nobody realized quite know how big a problem it is.

Can there be a clear picture of the scope and scale of this challenge in Ontario? And then as AMO officials like Lindsay started learning more, the sheer scale of the problem became, as she put it, “deeply troubling.”

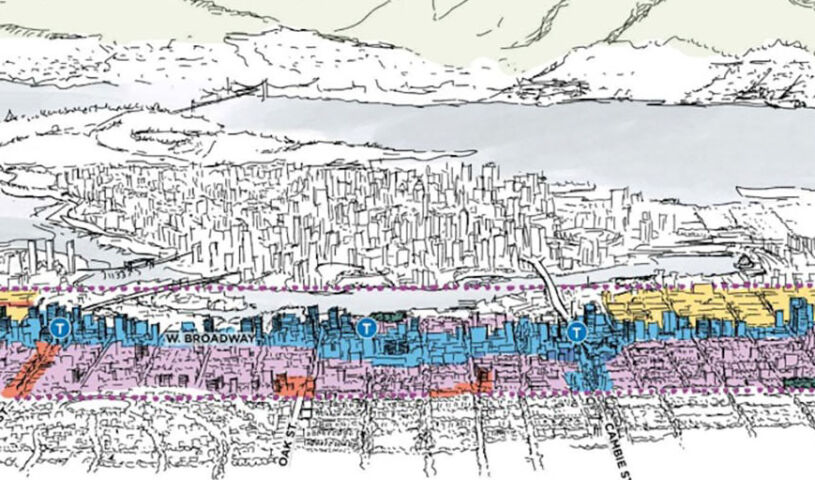

The majority of homeless individuals live in urban centres in southern Ontario. That said, homelessness is increasing fastest in rural and northern communities.

Since 2016, rural homelessness has increased by over 150 per cent, compared to a 50 per cent average rise across all communities. In Northern Ontario, homelessness has surged by an estimated 204 per cent, four times faster than in Southern Ontario.

Almost 50 per cent of the chronic homeless population in some communities are Indigenous, reflecting the enduring effects of colonialism.

The statistics contained in the report are almost too difficult to fully comprehend. For Lindsay, the number she said struck her the most was the 25 per cent increase in homelessness in Ontario just over the past two years.

“We’d been hoping that coming out of the pandemic there had been some additional investments and maybe we were at least kind of stemming the tide,” Lindsay said. “But what this report reveals is that’s absolutely not the case.”

Fiscal Realities, Political Questions

Recent provincial investments in homelessness, Lindsay said, are appreciated but inadequate. The $50 million allocated for affordable housing is three per cent of what municipalities alone spent on housing in 2024. In addition, $20 million in additional shelter funding is two per cent of the total spending on shelters in Ontario in 2024.

The study showed that $11 billion over 10 years would refocus investments into capital, increase focus on prevention, and create more than 75,000 new affordable and supportive housing units.

Lindsay acknowledges that $11 billion “is a big number.” But she also said AMO isn’t telling the province what it needs to do.

AMO’s study aims to enhance the province’s knowledge and assist officials in making evidence-based decisions. Lindsay stated AMO’s goal was to credibly illustrate the scale of the challenge and its realistic impact on municipalities and their budgets.

Lindsay highlighted that municipal spending on affordable housing increased by $900 million annually from 2020 to 2024. Meanwhile, the provincial investment grew by only $40 million.

“We just really wanted to put into perspective some of the investments that the province has been making because while absolutely every bit counts, it’s really important that everybody really has a shared understanding of how big the issue is and what it’s really going to take to make a difference,” Lindsay said. “We’re really proud of the fact that this data is so comprehensive and is so robust from a statistical perspective to provide a foundation going forward for evidence-based decision.”

Fear for the Future

While the majority of those experiencing homelessness are adults, nearly one quarter of chronically homeless Ontarians are children (0-15) or youth (16-24).

Those numbers, Lindsay said, are not only “deeply troubling,” but also surprising for the team at AMO.

Chronic homelessness is defined as people who have been homeless for six months or more in a year or for 18 months or more in over a three-year period. At one time, Lindsay said, youth weren’t seen as part of that population.

But now, to have youth be fully one-quarter of the chronically homeless population in Ontario is “staggering” she said. And the reality is this includes both youth who are a part of homeless families, and also those who are unaccompanied.

“It really is something to take notice of with our child welfare partners and the provincial government, “Lindsay said. “On that front, there’s been a lot of criticism about the Ontario Child Welfare system recently. So, we’re hopeful that this will be yet another piece of evidence that can help to feed thinking and decision making on that front.” MW

✯ Municipal World Executive and Essentials Plus Members: You might also be interested in Sébastien Labrecque’s article: Utilizing real estate conversion to boost housing supply.

Sean Meyer is digital content editor for Municipal World.

Related resource materials: