Are you smarter?

The Survey

In February, MW partnered with Juice Inc. to conduct an Are You Smarter survey to determine if people felt that they lost some of their intellectual capacity around certain people.

The research is curious in answering two things:

- Do municipal workers lose access to their smarts around certain people, and if so, why?

- For those who are able to retain their smarts around all people, how do they do it?

We thought you might be curious about these things too given how much can be at stake when employees lose their smarts.

A Bit of Context

Last month’s issue of Municipal World explored one way we lose our smarts: exhaustion. If you are engaged but exhausted, dedicated but depleted, the first thing you lose is access to your executive function – the ability to focus your attention, regulate your emotions, connect the dots, and make smart decisions.

For decades scientists have been pointing to a second way we lose our smarts: deprivation. The word may sound severe, but the experience is quite common. When we feel deprived of our driving needs, (belonging, security, freedom, significance or meaning) a fear response is triggered and emergency ops thinking kicks in. Survival becomes our primal goal and our thinking becomes simplistic, extremist, and impulsive. In other words, our thinking becomes very binary.

Perhaps you’ve experienced a conversation in which you felt unduly attacked and you found it hard to get your point across. Twenty minutes later you’re driving down the road and you have a flash of insight: you know exactly what you should have said in the conversation. This experience is surely to bring frustration along with it. Why wasn’t that comeback there for you in the argument? Because your brain felt deprived of respect, acceptance, and psychological safety. Instead, binary thinking kicked in.

When this all or nothing, now or never, you’re either with me or against me state of mind takes over, you lose access to the ability to:

- detect what matters most

- pick up on vital nuances

- connect the dots

- see what’s possible

- anticipate down-stream implications

These are the knowledge worker’s power-tools housed in our executive function. Let’s face it, losing access to these capabilities, innovation, integrative planning, and value-creation are virtually impossible. Organizational life can be rife with behaviours that trigger these kinds of shutdown.

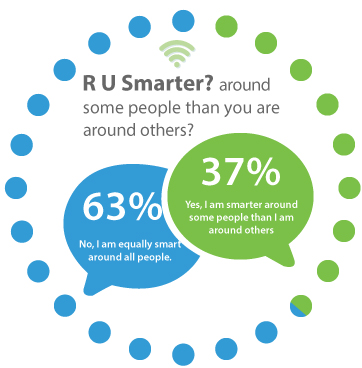

We have polled many organizations over the past two years and our research has revealed that on average three out of every four people say, “Yes, I am smarter around some people than I am around others.” So we were very curious to learn what the response would be inside the municipal environment. What we learned surprised us. But first, a bit of how the survey was conducted.

11,000 invites were sent out to partake in the survey. 1,194 people responded from municipalities across Canada. We ended up with a broad range of ages, levels, roles, and tenures providing us a rich demographic from which we could draw insight. A brief of the results are provided below.

The Result May Surprise You

Our work in health care, finance and other sectors has consistently revealed that peoples’ ability to access their intelligence is highly dependent on the behaviours of those they interact with. We’re accustomed to only 25 percent of respondents answering, “I am equally smart around all people” and 75 percent answering, “I am smarter around some people than I am around others.”

Surprisingly, the results were almost a direct inverse of the results we have found in the private section with 63 percent responding no to the first research question and 37 percent responding yes.

To visualize, picture a departmental meeting of twenty people. 13 of them feel they can access their smarts no matter who they’re interacting with and 7 feel they lose their smarts when interacting with certain people.

Surprisingly, the results were almost a direct inverse of results we have found in the private sector with 63 percent responding no to the first research question and 37 percent responding yes.

Males are more likely than females to say they are equally smart around all people (69 percent males/53 percent females). And, the older a man gets, the more he feels this is true. 77 percent of men who are 60 and older say their intelligence is not dependent on who they interact with, whereas only 50 percent of young men (18-25) make this claim.

Combining gender and age, intelligence becomes highly variable. 67 percent of females (18-25) say they are smarter around some people than they are around others.

There’s one interesting group of outliers. A whopping 83 percent of 26-34 year old men say they can access their smarts no matter who they’re dealing with.

Now let’s picture a different kind of gathering: a council meeting. Who keeps their smarts and who loses them? An astonishing 77 percent of mayors and council members say they keep their smarts no matter what, while only 58 percent of commissioners and CAO’s say they can keep theirs. One could imagine occasions when passionate council members feel their smarts are incontestable, and pose complex questions to commissioners and CAO’s. Municipal leaders, caught in the political crosshairs, may lose access to their smarts and struggle to produce a satisfactory response.

How people lose their smarts

We asked people, “Why are you smarter around some people than you are around others?” Of the 442 people who say they lose their smarts around certain people:

- 17% say the reason is hierarchy – “People outrank me”

- 11% say they feel criticized or judged

- 10% say they don’t feel acknowledged

- 9% say they don’t feel engaged in the topic

- 9% say they don’t feel people are interested in what they have to say

Here are five things you could do to help allow people to reach their full intellectual capacity:

- Don’t emphasize your rank: approach co-workers as partners.

- Practice non-judgmental conversation. Resist the temptation to jump to conclusions.

- Acknowledge what matters most to your partner rather than jumping into what you want to say.

- Focus on what matters most to your listener and frame the topic to address that.

- Demonstrate intense interest in what your co-workers have to say.

What gets left on the table?

We asked people, “If the people who make you feel smart get 100% of your best thinking, what percentage do people get when you feel less smart?”

The average response was 60%. It is difficult to grasp the implications of this finding, but one thing is sure; if one in three municipal workers feel unable to offer 40% of their best thinking, several notable things could be impacted including safety, quality, innovation, value-creation and the customer experience.

Let’s be clear, there are two issues here:

- Game-changing bits of information left unused.

- A third of the workforce feeling they can’t contribute – that their best stuff is bottled up inside them.

How people keep their smarts

The great news is two-thirds of municipal workers feel they can access their smarts around all people. The survey revealed four key ways people keep their smarts – all pointing to the importance of belief and skill. Of those who responded, “I am equally smart around all people,”

- 57% said, “I’m confident in my intelligence.”

- 18% said, “I am skillful at showing up.”

- 14% said, “I don’t let others define me.”

- 9% said, “I can regulate my emotions no matter who I’m dealing with.”

In our resilience work, we show people how building belief and regulating emotions create a bounce-back imperative that allow them to thrive, even in the midst of a disruptive political climate. The results above appear to indicate that two-thirds of municipal workers have acquired these traits of resilience. You may wish to ask yourself if this is what you witness in your department.

There is one caveat we need to mention. The qualitative data revealed several responses like the following:

“I.Q. is objectively defined. It doesn’t change based on one’s circumstances.”

“How can intelligence fluctuate according to context?”

These responses indicate that people may have misinterpreted the intent of our question. The Are You Smarter? survey is really asking, “Are you able to access more of your smarts in the presence of some people than you are in the presence of others?”

It’s too early for us to know, but it’s possible that functions with more analytical workers (e.g., I.T., engineering, accounting) may very literally interpret the question as, “Does my intellect change when I’m with certain people?” whereas functions with more intuitive workers (human resources, marketing, communications) may interpret the question as, “Do I feel smarter when I’m with certain people?”

It is possible that if we had asked, “Are you able to access more of your smarts in the presence of some people than you are in the presence of others?” we would have seen different results.

Conclusion

The results gathered from this survey can help to highlight barriers that municipal employers can work on with their employees to overcome not applying their full level of intelligence. To view full RU Smarter Report, please visit www.juiceinc.com/ru-smarter. In the next two issues of MW, we will show you how to:

- Keep your smarts in any situation.

- Develop a leadership style that enables people to keep their smarts.

- Help your colleagues keep their smarts in any situation.

as published in Municipal World, April 2017